Vladimir Sorokin – Book

March 28, 2024Unsolicited WhiteBox Open Call

May 1, 2024

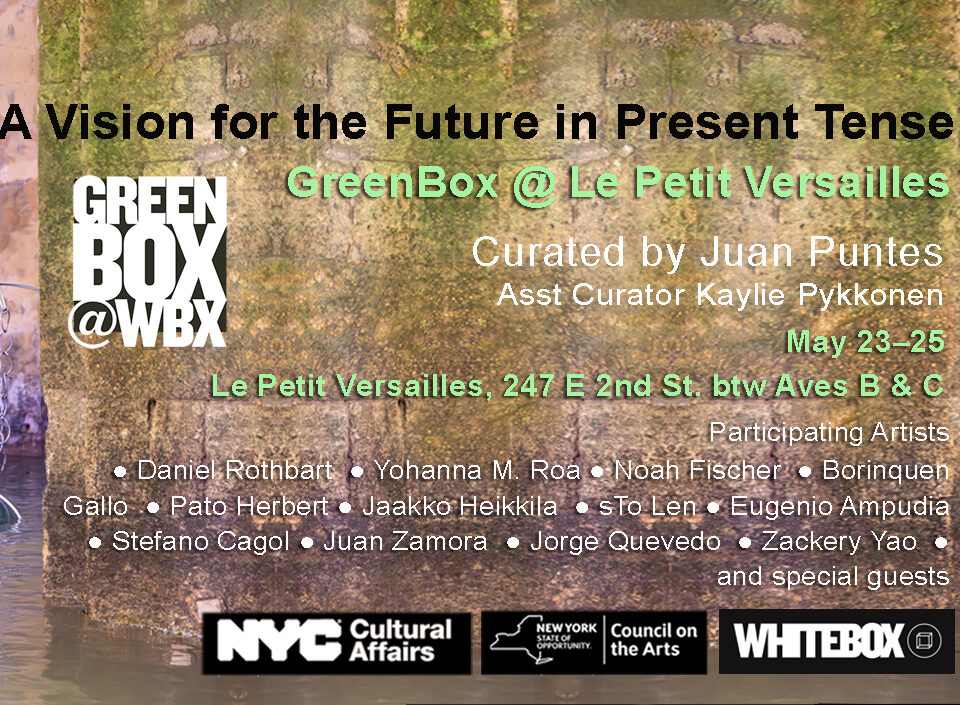

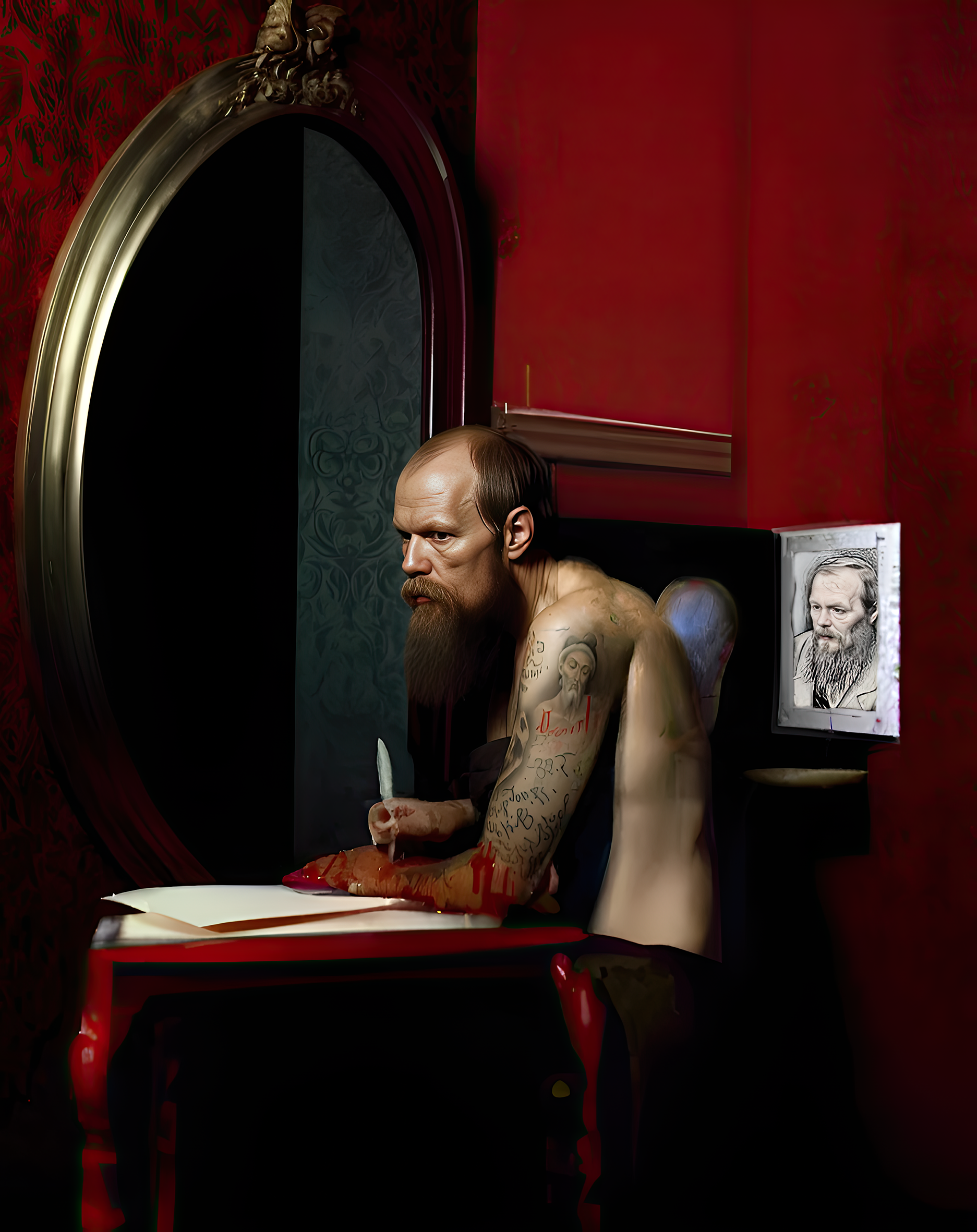

Vladimir Sorokin's exhibition BLUE LARD #cancelrussianculture is a bold experiment that combines the great legacy of classical literature with innovative AI technologies. The exhibition's title, Blue Lard, refers to Sorokin's iconic novel in which cloned Russian literary classics are transformed in a Siberian laboratory, giving birth to a unique product known as "blue lard." This everlasting Lard accumulated inside the bodies of the writers during the writing process—in this case of the clones of famous Russian writers from Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky to Akhmatova—those clones look almost like their human originals but at this time and place, they remain less than human – and, thus, monstrous." B. Groys.

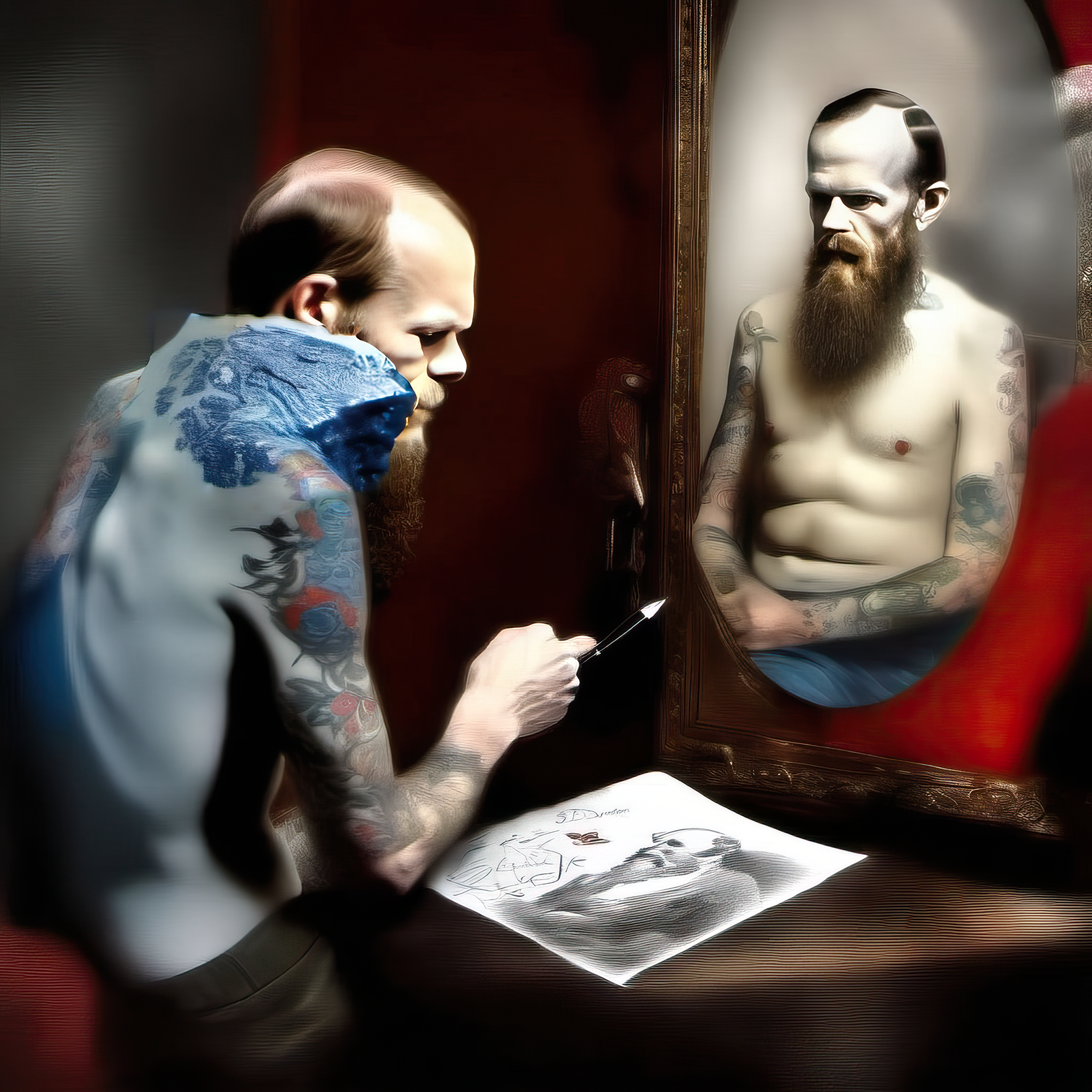

Fyodor Dostoevsky

Self-portrait cloning itself

Blue Lard - Press Release

The Monstrosity of Zeitgeist

Boris Groys on ‘Blue Lard’, by Vladimir Sorokin at WhiteBox Art Space

April 2 – May 4, 2024

The writer is the last artisan in the middle of an industrialized world. Writing is a purely manual activity – pushing the letters one after another on the sheet of paper or the screen of a computer. The usual position of the body of a writer is unhealthy. It is deforming the human body. In his novel “Blue Lard” Vladimir Sorokin underscores this manual, corporeal character of writing. The novel describes a farm in which the blue lard is produced. It becomes accumulated inside the bodies of the writers during the writing process – in this case of the clones of famous Russian writers from Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky to Akhmatova. And the blue lard is a valuable substance because – even after being removed from the writers’ bodies - it keeps the same temperature and consistency, thus, resists the general process of entropy. The clones look almost like their human originals but at such moment they are not quite human – rather monstrous.

One may ascribe this monstrosity to the imperfect cloning technology but, more plausibly, this monstrosity can be interpreted as a manifestation of total submission and the reduction of the writers to the process of mere writing. Paul de Man said about literary writing: “Writing always includes the moment of dispossession in favor of the arbitrary power play of the signifier and from the point of view of the subject, this can only be experienced as dismemberment, a beheading or a castration.”(1) In Sorokin’s novel this act of dispossession is described as a removal of the blue lard. But, as readers, how can we imagine the writers’ clones? Of course, we have a vague knowledge of how these writers did look like. Their images can be easily found on Internet or on the covers of their books. And, of course, from the reading of the novel we know that the clones were deviating from these writers’ standard, publicly established images. Nevertheless, the novel left a lot to the imagination of each reader.

Now Sorokin offers his own visual interpretation of the novel – and, thus, as it seems, establishes his own, authorial, aesthetic, and authoritative vision of its protagonists. However, from the beginning of his work as a writer Sorokin was aware of the death of the author and crisis of the writer’s authority. In his writings Sorokin always plays with different literary styles – from the Russian realistic 19th Century prose and official literature of the Soviet era up to the different modernist styles. He does not invent his own “subjective” style but develops a very idiosyncratic and easily recognizable use of well-established literary styles. His visual depictions of Blue Lard’s imagery expand this play on a field of artistic styles – namely, they are produced in collaboration with AI.

Speaking about AI, it is common to find the use adjectives like ‘inhuman’ or ‘post-human’ in the annals of contemporary media. However, there is nothing inhuman in the production of texts or images with the help of AI. The artist formulates a prompt, and AI realizes this prompt using a storage of already existing – humanly produced - images to which it has full access. As a text or image producer, AI is defined by the grade of its training, sophistication of its technology but also – and maybe, first – by the historically accumulated mass of texts and images with which AI operates. As history moves onwards, this mass of texts and images is changing – some images may be added, some images may get lost. So, if as an artist I write a prompt and the AI produces an image prompted by this prompt I can immediately see how my prompt is understood and interpreted at this historical-particular moment – not by an individual or a group but by the whole civilization in which I live. AI is nothing else but the embodied zeitgeist. And prompting this zeitgeist- machine I become able to analyze and diagnose the moment in history of which I am a contemporary.

The AI can process a huge amount of already existing texts and images whereas as writers, readers, artists, or spectators we tend to live in a cultural bubble. A major part of the cultural heritage – be textual or visual –escapes our knowledge. So, one expects that AI being able to process much bigger portions of existing information, will respond to a prompt with answers that would reflect an already accumulated mass of texts and images better than every individual writer would be able to do. Today, the prompting seems to be the only way to start a dialogue with this “objectified culture” – the embodied zeitgeist.

In his books and visual artworks Sorokin initiates precisely such a dialogue with zeitgeist. Zeitgeist being neither a vox populi nor, as they of late, “the hive mind”. Zeitgeist is not unified, does not speak with one voice. It is, rather, full of ruptures and inner contradictions. It has dark, violent aspects and hidden areas that are dangerous and repulsive. One can say that zeitgeist is monstrous because it is a combination of heterogeneous linguistic and visual body parts. As a writer Sorokin was always aware of this monstrosity of zeitgeist and attentive to its dark areas. Now he demonstrates the same approach as a visual artist. When I speak about monstrosity, I do not mean necessarily the mass-cultural monsters who are able to set everything on fire with one glance of their eyes or sweep everything away with their tail or tongue. Sorokin’s monsters are passive monsters.

They are monsters because they demonstrate themselves in an environment that is foreign to them. Their own culture and milieu have disappeared. Like the books that they have written, they become reproduced – cloned – far beyond their own historical time. Thus, they are doomed to write ever further in their already well-known manner, an occupation that obviously has no sense in their new environment. However, Sorokin suggests that for humans to live in the Anthropocene does not only mean to poison the environment with the by-products of their activity but maybe also produce something still unknown but valuable – something that can enrich the material composition of the Universe. Not mere writing, but Blue Lard.

- Paul de Man, Allegories of Reading: Figural Language in Rousseau, Nietzsche, Rilke, and Proust (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1979), 296.