Taller Boricua, From ArtWorkers Coalitions through today

April 27, 2023

Chin Chih Yang

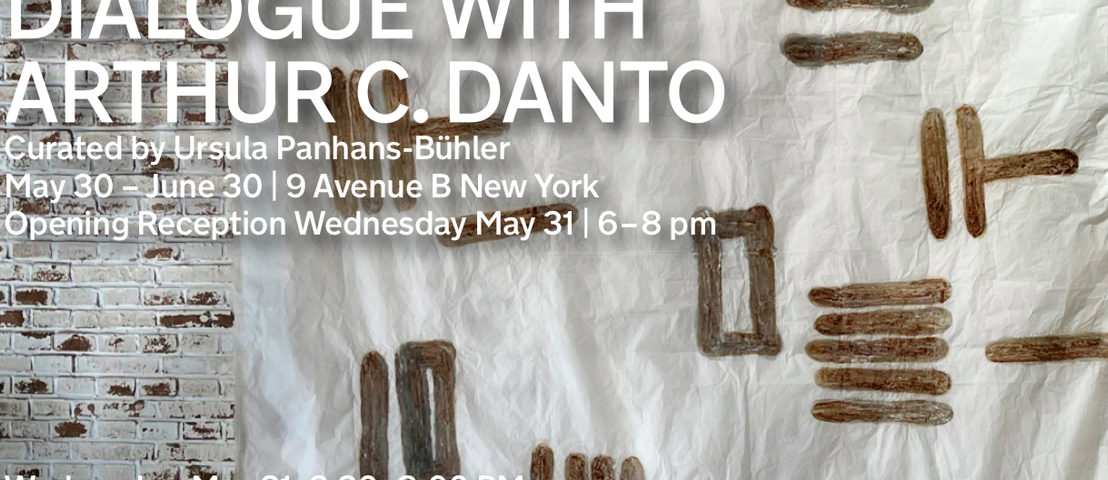

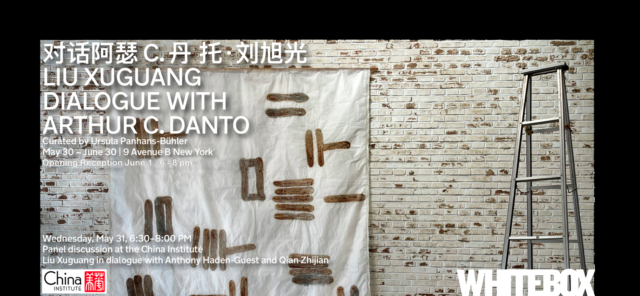

June 27, 2023Curated by Ursula Panhans-Bühler

June 1 – June 30, 2023

Opening Reception: Thursday June 1st, 6 – 8 PM

Link to China Insitute: Meet the Artist: Xuguang Liu on His Exhibition–Dialogue with Arthur C. Danto

At the turn of the last millennium, American philosopher Arthur C. Danto’s book “The Transfiguration of the Ordinary”, published in 1981 and long since notorious in its essence, triggered fierce debates among Chinese artists and critics. “New York Danto” became the epitome of postmodern questioning of art. Ironically, it was precisely the time when Marcel Duchamp’s art was welcomed in China with impartiality, enthusiasm and humor, free of any tendency towards iconoclasm.

Liu Xuguang completed his PhD at Beijing’s Tsinghua University with a “Theory of Essence Consciousness”, subsequently he elaborated this concept during art study visits to Japan. His research was based on a single character from the oldest Chinese character tradition, marks of “bu” found on Chinese bone writing. On the basis of this character he created works, often using large sheets of Rice paper, on which he drew a dense web of “bu” marks, drawn with oily earthy work ink and iron dust made himself. These works may seem abstract to Western viewers, but they are not at all. The lively vibration of all the “bu” marks follows a single direction, but none of it is absolutely the same as the other or submits to a grid. Thus they become the epitome of a many-voiced foundational act of civilization that translates direct verbal exchange into the permanence of objectifying signs, a new, social form of memory. His search for the “Essence of Consciousness” is therefore not a regressive longing for the origins, but a link of contemporary culture with its foundations, still handed down in China.

The works, which Liu Xuguang created during the three years of the worldwide Corona pandemic, mark a transition to a new dimension within his art. Reading literary, poetic or philosophical texts, one enters into an inner dialogue with the authors. Danto’s proclamation of the end of postmodern “commonplace art” through its “transfiguration” into philosophy triggered in Liu Xuguang the desire to give this inner dialogue an artistic form. Eventually this came out as an extensive series of drawings. He had dialogues not only with Western and Eastern theoretical and poetic philosophers, but also with two important psychoanalysts: Sigmund Freud, the founder of Psychoanalysis, and Jacques Lacan. Both have sharpened our attention to the repressed by rationalizing philosophical theorizing: namely, the unconscious, contributory in all poetic artistic intuition, and so also in Liu Xuguang’s dialogues.

As he himself explains, his drawing dialogues resulted from the feelings that the texts of the dialogue partners had triggered in him. However, he based their configurations on elements that go back to the 8 trigrams of early Chinese culture, which denote algebraic, cosmological, as well as opposing forces of world’s Nature. Each drawing shows a different numerical configuration, which now act like scores of a musical theme. We feel them with our eyes and thus participate in the sensitive dimension of the respective dialogue.

Liu Xuguang has rightly noted that Danto’s “end of art” actually meant the end of a history of art that since Vasari repeatedly was glorified as a history of progress. In this respect, I recommend a reference to one of Liu Xuguang’s dialogue partners, Mo Zi from the 4th century BCE, the “time of the contending empires”. Mo Zi described the relationship of the present to the past in this way: What we consider as “past” was innovative in its time. We should take this as an encouragement to own innovations in our time. A Neon tube inscription, mounted in 2000 by Italian artist Maurizio Nannucci on the attic of the Berlin “Altes Museum”, “All Art has been contemporary”, corresponds to such an attitude.

Let’s add a final comment on Liu Xuguang’s remark about the role of feelings in any artistic discourse, a role that also applies to their rationalizing suppression: In the Yi Jing, the “Book of Changes”, the 36th hexagram is designated “mingyi”, “hidden brightness”. Shouldn’t the way, how each of Liu Xuguang’s dialogue configurations deal with the space of the rice paper’s iridescent light, be related as well to this “mingyi” ?

序

在上个千年之交,美国哲学家阿瑟·C·丹托的《平凡的转变》⼀书于1981年出版,其本质早已臭名 昭著,在中国艺术家和批评家中也引发了激烈的争论。“纽约丹托”成为后现代艺术质疑的缩影。具有 讽刺意味的是,正是在这个时候,马塞尔·杜尚的艺术在中国受到了公正、热情和幽默的欢迎,没 有任何偶像崇拜的倾向。

刘旭光在北京清华⼤学以“论质觉”完成了他的博⼠学位,随后他在⽇本的艺术考察中阐述了这个概 念。他的研究是基于中国最古⽼的汉字传统中的⼀个字,即中国⾻⽂中的“⼘”字。在这个字的基础 上,他创作了⼀些作品,经常使⽤⼤张的宣纸,在上⾯画出密密⿇⿇的“⼘”字,⽤油性的⼯作墨和⾃ ⼰制作的铁粉绘制。这些作品在西⽅观众看来可能是抽象的,但它们根本不是。所有的“⼘”标记的⽣ 动振动都遵循⼀个⽅向,但没有⼀个是绝对相同的,或服从于⼀个⽹格。因此,它们成为⼀种多声 部的⽂明基础⾏为的缩影,将直接的语⾔交流转化为对象化符号的永久性,⼀种新的、社会形式的 记忆。因此,他对“质觉”的寻找并不是对起源的倒退式的渴望,⽽是将当代⽂化与它的基础联系起 来,仍然在中国流传着。

这些作品是刘旭光在新冠⼤流⾏的三年⾥创作的,标志着他的艺术向⼀个新的层⾯过渡。阅读⽂ 学、诗歌或哲学⽂本,⼈们进⼊了与作者的内⼼对话。丹托宣布后现代“通俗艺术”通过“转变”为哲学 ⽽结束,这引发了刘旭光将这种内⼼对话赋予艺术形式的愿望。最终,这变成了⼀个⼴泛的绘画系 列。他不仅与西⽅和东⽅的理论和诗学哲学家进⾏了对话,⽽且还与两位重要的精神分析学家进⾏ 了对话:西格蒙德·弗洛伊德,精神分析的创始⼈,和雅克·拉康。两⼈都通过理性化的哲学理论 使我们更加关注被压抑的东西:即⽆意识,在所有的诗歌艺术直觉中都有贡献,在刘旭光的对话中 也是如此。

正如他⾃⼰解释的那样,他的绘画对话来⾃于对话伙伴的⽂本在他⾝上引发的感受。然⽽,他基于 他们的配置,追溯到中国早期⽂化的⼋卦,表⽰代数,宇宙学,以及世界⾃然的对⽴⼒量。每幅画 都显⽰了不同的数字配置,现在它们就像⾳乐主题的乐谱。我们⽤我们的眼睛来感受它们,从⽽参 与到各⾃对话的敏感层⾯。

刘旭光正确地指出,丹托的“艺术的终结”实际上意味着⾃⽡萨⾥以来⼀再被美化为进步史的艺术史的 终结。在这⽅⾯,我建议参考刘旭光的⼀个对话伙伴,公元前4世纪的墨⼦,即“帝国争霸的时代”。 墨⼦是这样描述现在与过去的关系的:我们所认为的“过去”在其时代是创新的。我们应将此作为⼀种 ⿎励,在我们的时代拥有创新。2000年,意⼤利艺术家默⾥奇奥·纳努奇在柏林“⽼博物馆”的阁楼上 安装了⼀个霓虹灯管铭⽂,“所有艺术都是当代的”,与这种态度相呼应。

让我们对刘旭光关于感情在任何艺术话语中的作⽤的评论做最后的补充,这种作⽤也适⽤于对感情 的合理化抑制:在《易经》中,第36卦被称为“明夷”,即“隐明”。刘旭光的每⼀个对话配置如何处理 宣纸的五彩光芒的空间,难道不应该与这个“明夷”有关?