Trapped in Wuhan 2020

February 18, 2020

EXODUS II: Unhinging the Great Wall: Chinese Art Revealed, East Village NY, 1980s

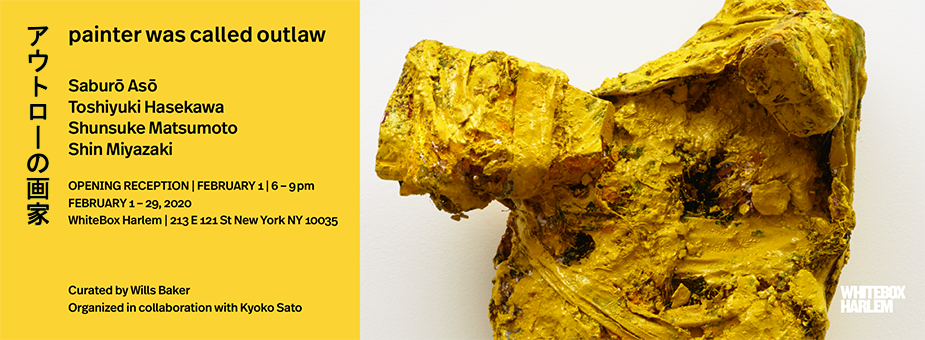

February 25, 2020Curated by Wills Baker

Organized in collaboration with Kyoko Sato

February 1 – 29, 2020

WhiteBox Harlem is pleased to present Painter Was Called Outlaw, curated by Wills Baker. The exhibition introduces four Japanese artists, the early 20th-century expressionist painter Toshiyuki Hasekawa (1891 – 1940), inter-war painters Shunsuke Matsumoto (1912-1948), and Saburō Asō (1913–2000) along with postmodern paintings and sculptures by Shin Miyazaki (1922 – 2018).

All four artists’ lives intersected in the 1930s; as a young art student, Shin Miyazaki befriended Toshiyuki Hasekawa, who gave him an oil landscape, (Scenery with Wagon, 1932, oil on canvas) depicting an ox dragging a heavy bale – the mentor imparted the prophetic piece which remained in Miyazaki’s possession his entire life. In 1932 before the war and bombing raids, growing dissatisfaction with the conservative climate of the Pacific Art School led Matsumoto Shunsuke to leave and establish a cooperative studio in Tokyo. During this time he met Saburō Asō and Aimitsu who were working in surrealist and expressionist styles openly in rejection of the mounting populism and military ambitions of the Imperial government; together in 1943 they would later found the Shinjin-Gakai (Emerging Artists Society) as an act of counter cultural comradery. Painter Was Called Outlaw collectively shows artists in confrontation with oppressive social forces, isolation, the dehumanizing conditions of war and mass violence, but also the dignity, power, and courage of artmaking as an expression of freedom.

The exhibition draws its title from the biography of Toshiyuki Hasekawa, (Painter was called outlaw, written by Kazumasa Yoshida, Shogakukan Press.,

2000), whose radical expressive paintings documented Tokyo’s rapid industrialization with bold, quick brushwork empowered by experimental breakthroughs in late 19th-century western-style painting. Hasekawa’s daring vision in the face of the artistic elite made him an unapologetic representative of individualism in an environment that was, by nature, hostile to it. Hasekawa traversed the landscape of Tokyo’s working-class communities, locating subjects in fellow artists and night dwellers while living in the underground worlds of brothels and street-cafes. Rejection by the Nikakai artist association, which would have offered him the support of a professional network left Hasekawa impoverished for the duration of his lifetime. Despite this pitfall, he continued to paint and remained unapologetically devoted to his ardently rebellious style until his death on the streets of Tokyo in 1940.

In 1936 Matsumoto Shunsuke and his wife Teiko started a monthly magazine of essays and drawings called Zakkichō (Notebook), the periodical included submissions by fellow artists including Saburō Asō and established writers across the ideological spectrum. By the last issue in 1937, young Matsumoto was beginning to express alarm at the rising tide of intolerant attitudes stemming from ultranationalists. Reproductions of all 14 issues are on view; altogether, the copies reflect the evolution of Matsumoto’s civic conscience and his attempt to expand a compassionate and pluralistic worldview in response to escalating political discord.

Japanese modernism and its wartime cross-currents exemplify the painstaking development of personal expression and creativity as it was challenged, censored, and repudiated by social, totalitarian, and militaristic forces that congealed in the 1920s and 30s. Leading up to WWII, young avant-gardes like Shunsuke Matsumoto (1912-1948) and Saburō Asō (1913–2000) were censored by the propagandist mechanism of the new hybrid military government. Most artists complied to produce and promote images of a victorious homogenized nation-state. Matsumoto and Asō strove to represent the truth, the actual conditions of suppressed and disadvantaged people in their society drained of verve. The war deepened, and bombing raids claimed the lives of Japanese citizens, and yet they painted in spite of it. Their resistance in the face of death was re-affirmed with each creative act of protest. As if a declaration of survival against the suffocating conditions, Saburō Asō conceived a style of thickly painted surfaces, on which creating an image was an iterative struggle. He depicted the transformation of the Japanese citizen under military rule by smothering his subjects in gestural red and black diminishing their stature and presence. On view in the exhibition is Asō’s 1950 portrait entitled, Youth, it may be read as a poignant encapsulation of the totalizing hardships endured by the Japanese people and once optimistic members of his own circle.

In January 1941, a long article in the art magazine Mizué detailed the aesthetic views of an organization new to art discourse — the Imperial Army. The article made explicit a new authoritarian threat to self-expression and artistic freedom. Three months later a second essay in Mizué titled, “The Living Artist” (“Ikiteiru Gaka”), by the young painter Matsumoto Shunsuke, offered an impassioned reply.

The article was Matsumoto’s manifesto defending humanism and rejecting authoritarian control over the arts. The article cost him his career and nearly his life; yet, by defending personal liberty, his words paved the way for future artists. His bravery is remembered today, and although he did not survive to witness the outpouring of cultural experimentation and creativity by young Japanese artists in the postwar years, his legacy directly contributed to it.

Following forced conscription, Shin Miyazaki was sent to Northern China and taken prisoner of war by Soviet forces in 1945. He was held captive in Siberia until 1949, four years after the war had ended. His later work recalls the Soviet prison camp by way of figural and earthbound images rising against the thick materiality of paint and plaster, asserting life against a harsh, unnamable weight while compounding the technical and emotive power of his predecessors (Asō, Matsumoto, Aimitsu, and Hasekawa).

Miyazaki’s practice acknowledges one of the most painful legacies of the 20th century. Still, it does not project anger or accusations directed at others or desperate, anguished thoughts directed at the self. Instead, it reminds us of compassion for human beings and admiration for the resiliency of life, and, while he suffered greatly, he never relinquished his will to create.

Painter Was Called Outlaw pieces together a group of artworks that serve as surviving reminders of the human cost of war and the mobilizing impact creativity can have in opposition to oppressive policies. We are facing a moment when war-mongering and exclusionary attitudes are on the rise. This exhibition is an attempt to retell the stories of individuals who paid with their lives for rejecting views that have yet again resurfaced globally. Painter Was Called Outlaw aims to counter the pressing political realities of our time with the works of courageous artists who endured and stood for human dignity.

This exhibition is made possible by The Jonathan D. Lewis Foundation and Bishop Family Foundation.

Special thanks to Dr. Laura Hein of Northwestern University’s Department of History, Harvard University’s Department of East Asian Studies Doctoral Candidate, Mycah Braxton, Mark Zitelli, Jay Baker, Sayaka Kawazoé, Yūsuke Wakata and Sakurako Mizuno.