ZINAIDA: ARTREHUB

June 20, 2018

Tender Cities: Symbolism of a City

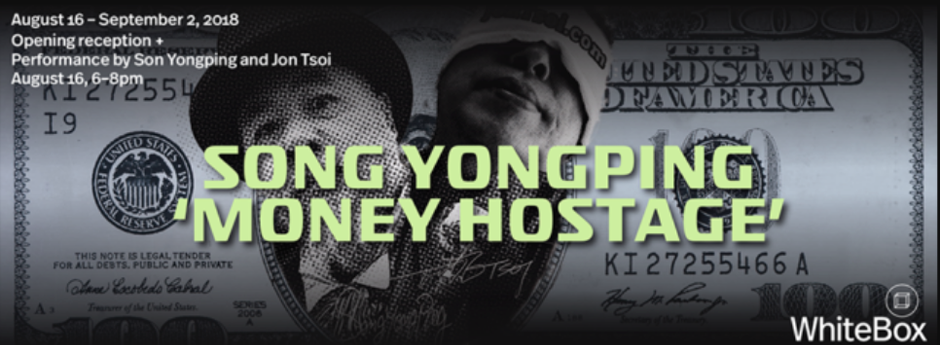

June 29, 2018August 16 – September 2, 2018

The presence of money as a subject matter and a symbol of the capitalist nature of the art world in particular in artists’ works have a long history that includes pieces ranging from Rembrandt to Chardin, Picasso to Warhol. AHG

WhiteBoxLab is pleased to present Money Hostage by Song Yongping a new resident of New York City with a participatory performance New York based artist by Jon Tsoi as one more chapter of a collaborative performance program between New York based Chinese artists and their mainland based counterparts. Inspired by the current state of accelerating money worship culture in China, Song Yongping seeks to communicate the idea of dollars being at once unusable and achingly desirable. He makes a statement about our relationship with money by turning the bills into aluminum prints, swapping the original American historical portraits by those of Mao, Karl Marx, a busty Passerby Woman and a grimacing Barak Obama adding verbiage, and eventually, wallpapering walls and floors with them.

“Money naturally plays as important a role in the functioning of the art world as it does in any other activity in which goods and/or services are exchanged. Often the process is straightforward – art is made, it is sold – but the higher you climb in the money tree, the more slippery it becomes. No accident. If the ways in which art moves money – and vice versa – can seem opaque and elusive, these are the characteristics that help keep the art economy afloat.

So, it’s no surprise that money is sometimes the actual subject matter of art. But artists don’t often use financial instruments – coins, banknotes, checks – just as handy borrowings from real life, the way Chardin laid a table with jugs, Cezanne used apples or Picasso his guitars, because money always implies story. As with Rembrandt’s early masterwork, Judas Returning the Thirty Pieces of Silver, images of the currency almost always bear a load of meaning. Many meanings, in fact, and often dark ones.

This is an area in which, as one might expect, the US currency rules. Warhol’s Dollar Bill series of 1961, which was part of the evolution of his silkscreen process, was a cool blast of Pop, being at once deadpan and exultant. Both within and outside the US the dollar sign is seen as a brand and the image of the bill is a flag. Usually a weaponized flag. Just as when Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin and their crew showered the traders in the New York Stock Exchange with dollar bills in the guerrilla theater action that launched the Yippie movement on August 24, 1967. And Richard Prince has used dollar checks in paintings, one of which the Gagosian Gallery turned into a billboard on the Sunset Strip, Los Angeles. But no artists, whether within or outside the US, have been as single-mindedly in the culture’s face, in their use of the dollar as Song Yongping.

Song was born in 1961 in Shanxi Province, Northern China. He graduated from the Tianjin Academy in 1983, set up as a painter, and joined a Beijing group, New Pictures of the Floating World, who were critiquing the materialism of Post-Maoist China, rather as certain of their contemporaries in New York were mocking the commodification of the art world. Song set out to make a career and by the end of the 90s he was doing well. It was then that both Song’s mother and father fell ill and he at once followed the directives of Chinese culture, which are humane, yes, but stern and demanding, setting aside brushes and paints, and dedicating himself to their care. He has stated that the weight was a heavy one, almost unbearable, but it was relieved by the purchase of a camera with which My Parents, unflinching portraiture of their failing lives. The closest parallel in Western photography has to be the portraits Richard Avedon shot of his father Jacob Israel Avedon, in 1971. Avedon accepted that these portraits had an element of performance and Song’s parents likewise participated in the making of theirs. Avedon’s father died two years after the pictures were taken, Song’s parents died in 2001. So back to work.

The body of work you will experience in Dollar Hostage is direct, indeed as obvious as a slap in the face, but stinging and resonant, especially appropriate to our simmering contemporary climate of tariffs, trade wars and widening wealth gaps, in the art world at least as much as anywhere.

Song replicates US dollars – a legally tricky action in the US, of course – turning the bills into aluminum prints, enlarging them, toying with them, acting as if tempting recipients to try passing them off, collaging portraits of Mao, Karl Marx, a busty woman and a grimacing Obama into the center, adding verbiage, papering walls and floor with them, making the dollar at once unusable and achingly desirable, less a currency than a universal wish-dream. Just, indeed, like the dollar itself. “Money is the eternal theme of human existence,” Ai Weiwei has observed. “Money is the most accepted criterion of survival and competition today.” He added – and excuse my translation of a translation – “Song Yongping’s money pieces are loaded with aesthetic and psychological meaning. They are a political expression of the money system today”. So onwards to Money Hostage and Song Yonping’s collaboration with Jon Tsoi.”

ANTHONY HADEN-GUEST

金钱人质

如同任何其他商品或服务的交易一样,在艺术世界里金钱自然也扮演着重要的角色。通常这个过程直截了当 – 艺术品被创作出来,然后被卖掉。但是毋庸置疑,在金钱这棵树上爬得越高,风险就越大。艺术与金钱的互相推动作用,其过程似乎模糊又难以捉摸,这是帮助艺术经济浮动的重要特性 ,所以金钱成为艺术品的主题就是意料之中的事了。

但是艺术家通常不会直接将金融工具 – 比如硬币、纸币、支票–作为不含深意的日常用品来描绘,如夏尔丹在桌上放的瓶瓶罐罐, 塞尚的苹果,毕加索的吉他一样,因为金钱往往暗示着故事。在伦博朗早期的代表作“犹大退还三十枚银币”中,银币的形象被注入了大量的 含义,其含义时常是黑暗的。

正如人们所预见的,在艺术领域中美元占有统治地位。1961年安迪霍夫的美元钞票系列,是其丝网印刷技术进化的一部分,亦是波普艺术的一次引人瞩目的爆发,作品中的形象既面无表情又眉飞色舞。在美国内外美金符号被看作是一个商标,而美元的图案则仿佛旗帜,时常是一个武器化的旗帜。1967年8月2号,阿比霍夫曼和杰瑞鲁宾在他们创建的流动剧场行动中向纽约股票交易所的交易员们挥洒美金钞票,标志了雅皮运动的开端。理查德普林斯在他作品中使用了美金支票的形象,其中一幅被高古宣画廊制作成了大型广告牌投放在了洛杉矶的落日大道上。但是没有任何艺术家,不管是美国之内还是美国之外,像宋永平那样如此专一地在文化层面上使用美金的形象。

宋永平1961年在中国北方省份山西出生。他于1983年从天津美院毕业。他给自己定位为画家,加入了北京的“新浮世绘”运动,对中国在后毛泽东时代的拜金主义进行了批判,正如纽约同时代的艺术家一样,他对艺术世界的商业化进行无情的嘲讽。

宋永平在90年代末即作为艺术家获得成功。但是他的父母那时都生了重病。他立刻按中国文化传统的规诫,放下了手里的画笔去全力照料他们,这是人性的呼唤,却也是极为严苛繁重的。他曾说过那段日子他担负了难以承受的压力,而这种压力在他买了一部相机后得到了释放和缓解,他为父母拍摄的撼动人心的系列肖像记录了他们日薄西山的生命。

西方摄影师的作品中最能与此相映成趣的应该算是理查德阿文顿在1971年为他父亲所拍的肖像。阿文顿的肖像中有表演的元素,而宋永平的父母也同样地参与了他们身份的刻画和表演。阿文顿的父亲在拍摄照片两年以后去世,宋永平的父母则在2001年去世,同年他重新开始工作。

“金钱人质”的作品对观者的体验或将非常直接,仿佛一记打在脸上的耳光,刺痛却震撼,在当下关税,贸易战争和财富不均的暗流涌动的经济气候之中这一主题极为贴切,在艺术世界里也好、或任何其他地方也罢。

宋永平在作品中复制并运用美元符号——虽然这在美国自然涉及到一定的法律问题——将美元改造成铝板印刷品,放大并玩弄这一符号,以假乱真的造型仿佛引诱着观者。他将毛泽东、卡尔马克思、丰满的女人像和扮鬼脸的奥巴马以拼贴的方式安插在美元钞票的中央、在其上写上胡话、用其糊墙和糊地板、将美元的形象贬低为不可利用却又同时显示其诱人之处,仿佛它已不仅是一种货币,更是一个普世的梦想。而这正是美元在当今人们心目中的形象。艾未未曾总结自己的观察道:金钱是人类存在的永恒主题,金钱也是当今生存和竞争最广为接受的标准。他又补充道—请原谅我对他的翻译所进一步做的翻译—“宋永平的金钱作品充满了美学和心理含义。它们是今天金钱系统的政治表态。”这一命题也延续到了宋永平和蔡江合作的“金钱人质” 上。

安东尼海顿