Black Zero: Performa 09

November 22, 2009Hans Breder: Inmixing

December 8, 2009Juanli Carrión

Curated by Blanca De La Torre

November 23 – December 8, 2009

Opening Reception: Tuesday, November 24, 6:00 – 9:00 pm

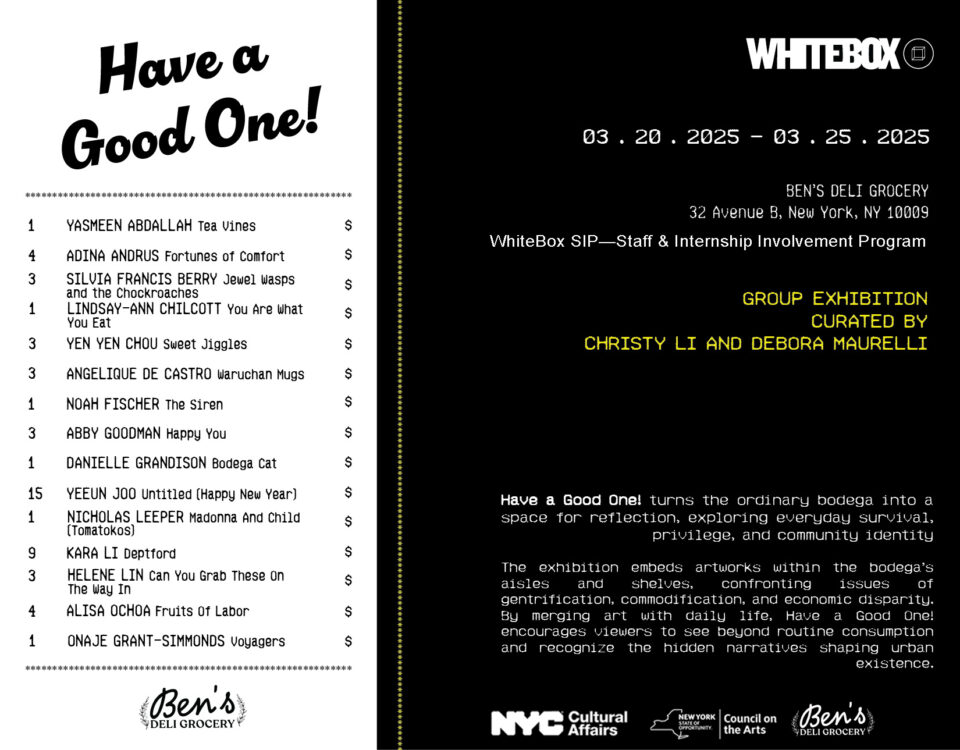

White Box is very pleased to present Juanli Carrión: ATLAS SHRUGGED in WHITE BOX PROJECTS space from November 23rd through December 8th, 2009. This exhibition of the Spanish artist Juanli Carrión, takes its title from the landmark 1957 novel Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand, exploring a dystopic America where the world’s leading innovators go on strike after feeling exploited by society, refusing to allow the rest of the world to use their ideas and investigations. On the occasion of Juanli Carrión’s first solo exhibition in New York at White Box Projects, the title is appropriated in an ironic way, as opposed to the Philosophy of Objectivism advocated by the novelist, in order to speak about dystopia in an alienated landscape of an undefined reality and time.

The representation of the contemporary landscape may be conceived as a reflection of spaces realized almost unconsciously, where the natural environment is perceived through and within the imperceptible process of transformation. In this depiction of ever-changing realities, the inert image loses an essential meaning, interchangeably becoming a subject and/or an object as subject.

Juanli Carrión dissects the landscape to speak about a contemporary dystopia, analyzing the potential beauty in an intermediate terrain between the natural and the artificial. Certain human traces are present in all of the photographs, either subtle or absolutely blatant, but always there, threatening. All of them contain implicit stories that may appear as vacant as the scenario that contains them.

His work references the iconic New Topographics movement, which epitomized a paradigmatic shift in American landscape photography. In concordance with their depiction of the maligned landscape, Carrión suggests a false consciousness of the real spaces that were probably never as pristine or idyllic as they may have once been in the social imaginary conscience. The artist repositions or eliminates the traditional mid-plane horizon; a perspective that throws the picture plane off balance and adds to a certain uneasiness of contemplation. Carrión’s photographs stand as a tragic reminder of what has been displaced by human development, blurring the distinction between cultural and natural landscapes.

With water acting as a leitmotif, Carrión avidly juxtaposes the man-altered landscapes with the idea of what those settings were or could have been without the traces of human exploitation. Obviously as the demands on the photographic medium since the New Topographics have radically changed, Carrión conscious usage of the light box format counteracts the otherwise laconic quality of the images. Nevertheless, a sense of disorientation sets in as you move in closer to discover a subtle movement in the water, which permeates the scene, leaving us with a kitsch-like sensation. This is reminiscent of the light boxes that typically decorate local Chinatown restaurants, giving another sarcastic nod to the individualistic capitalism championed by Ayn Rand. The destabilizing effect is further emphasized by the atmospheric humming sound heard from the light boxes. Each depicted environment underlines a tension between the conceptual strength of the images and their formal irreverence.

Despite the apparent opposition between the avant-garde and kitsch as argued by Clement Greenberg, Carrión’s work clearly defies and overrides any easy delineation between what is today considered kitsch and cutting edge, at far remove from what was once exclusively determined Avant-Garde. Moreover, the artist challenges the views of kitsch held by Adorno, as the parody of an aesthetic experience in relation to the cultural industry and its conception as a sub-product of the market. Carrión subverts this definition by taking an ironic stance in works that shift between explicit tackiness and implicit content, suggesting an apology of its own kitsch while illuminating a tangential redefinition of the new topography.